There is much talk today about the housing crisis across California. While the crisis is real and complex, it is most often addressed in a piecemeal and somewhat simplistic fashion. The issues facing communities in California are not just about having affordable housing for anyone that wants to live in a specific community. Housing and all its related policy areas is a large, complex topic not solved easily.

Over these next few weeks, we will be discussing policy areas that impact housing decisions and supporting legislation, and which should be discussed whenever housing policies are made locally or at the state level. Part 2 is about economic disparities and the role that dynamic plays in the housing crisis; and it is about whether or not increasing the number of market-rate units will actually solve the housing crisis.

Underlying the housing crisis in California are critical economic factors that must be addressed before we can solve the housing crisis in a productive manner, regardless of how many houses we do or don’t build. The economic disparities in our society are growing and are destructive. Wages have not kept up with prices of consumer goods and the general cost of living, most particularly the cost of housing, both ownership and rental. Until that is productively addressed, a growing segment of our communities will never be able to afford a living space of their own.

What follows are some data snippets gleaned from a variety of sources from Reuters to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. They demonstrate that no matter how you define it or explain it, no matter your political perspective, wages and entry and mid-level salaries are not allowing reasonable or timely home purchase or rental in tight markets like the immediate San Francisco Bay Area.

“For example, to buy a median priced home in various areas of New York City, Brooklyn and Manhattan especially, or in the San Francisco metro area, a buyer needs to spend between 120 percent and 95 percent of the average wage on mortgage payments.” Reuters, March 24, 2016.

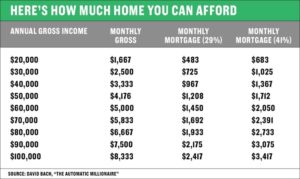

“…according to the Federal Housing Association, a good rule of thumb is that most people can afford to spend 29 percent of their gross income on housing expenses — as much as 41 percent if they have no debt,” Bach explains in his book, “The Automatic Millionaire.”

“Dramatically higher prices are partly why the typical homebuyer is now 44, whereas in 1981, the typical homebuyer was 25-34.” Emmie Martin, June 23, 2017.

“You’ll find the country’s most expensive rental markets in [San Francisco]. To afford a two-bedroom apartment, you’ll need to make at least $216,129 annually. While rental rates have increased in recent years, wages haven’t kept up. The median household income in the city is only $78,378.” Amanda Dixon, December 20, 2017. Percent change of a two-bedroom rental in San Francisco from 2015 to 2016 is 7.4%. Kathleen Elkins, August 15, 2016.

“Only 31% of SF households make more than $150,000 per year.” Derek Miller, February 20, 2018.

A January 19, 2016 report by Marian Tupy of reason.com demonstrates the complexities of analyzing the historical path of wages vs. cost of living. She makes a valid point that the “…expansion of non-wage benefits, fall in the price of consumer goods and rise in price of services, such as education and healthcare…” complicate the generally accepted data point that hourly wages have stagnated or declined since 1979. She further points out that the “average American” has seen certain “welfare gains” in the same period that should be included as part of the overall calculation, (e.g., “…houses are larger, healthcare better, and education more high tech…” than in 1979); and that In contrast, she also points out that “The cost of education, healthcare and housing has risen at a faster pace than total compensation.” What she fails to address in the totality of the calculation is that a vast majority of those on the lower end of the spectrum do not enjoy the “welfare gains” she identifies: they do not have access to healthcare except as might be accessed in an emergency room, are not privy to the “high tech education” opportunities, and cannot afford a house, larger or otherwise.

For a very good web-based presentation of the issues, check out CalMatters.

Taking all this into consideration, it is hard to argue that building more housing units will do much to allow lower wage earners and salaried workers to gain a better foothold on securing their own living space in their desired communities. True, more units on the market may cause a slight dip in pricing, but I would argue that such a dip will simply allow more high-wage/salaried earners to buy and/or rent in the desirable locations (i.e., provide opportunity to the pent-up, already-prequalified demand currently shut out of the market due to lack of inventory).

One could argue that at least more units will slow the thirst of landlords to seek higher and higher rents either at time of vacancy or by direct eviction of current tenants. However, I refer to the previous paragraph: more rental units will simply accommodate some, but not all, of the pent-up demand of the already prequalified renter willing to pay the higher prices because they can.

More units, built to address current market rate demand by their simple existence, will not provide affordable “workforce” housing to allow teachers and others to live in the communities in which they work, and to avoid the excruciatingly long commutes in which they are currently involved. A small number of “affordable” units as defined by HUD will not even make a dent in the population of lower wage earners and salaried workers desiring to move closer to their work.

It appears that the only way to comprehensively address the housing crisis, short of a tremendous recession in the housing industry, is with a comprehensive approach that makes housing prices overall more affordable, increases the inventory of available units, and increases the wealth of those at the lower end of the economic spectrum.

It depends a great deal on the political and philosophical priorities of those in elected office. If things are important like addressing global warming by controlling greenhouse emissions; having a healthy economically diverse community; perceiving value in having your teachers and other public servants live in the community in which they work; retaining young families in the community; reducing/eliminating homelessness…if these things are important, then the housing crisis must be attacked on multiple fronts including establishing an actual living wage for the area, quickly approving more housing units , partnering with banks and other financial institutions to structure workable financing for riskier lower income buyers, requiring and subsidizing higher numbers of affordable units, planning for and subsidizing workforce housing, equitably regulating rents, and developing comprehensive housing and social service programs for the homeless.

All good, but what is a living wage and for whom should it be paid? What are the elements of “homelessness” and how might communities address the issue? What right, if any, do communities have to limit the quantity of their residents? How do we reconcile unlimited growth with limited natural and essential resources like water? What role does quality of life play in communities and who defines it? Is higher density meant for every community? Are State-determined housing quotas working and are they realistic? Should government control the housing market place, and if so, how? How do we equalize education so that all children have access to a quality education and educational facilities? What is the impact of housing usurping open space and agricultural land?

On to Part 3.

Fran…will there be some suggestions at the end of this excellent review? Enjoying these blogs.

Working on it……Check out CalMatters at CalMatters.org

Filmizlesene ile hızlı film izleme fırsatını yakala, en yeni ve iyi filmleri Full HD 1080p kalitesiyle online ve bedava izle. Josef Sifford

https://mazda-demio.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6332

https://mazda-demio.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6397

https://myteana.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6666

Awesome https://is.gd/tpjNyL

Very good https://is.gd/tpjNyL

Good https://shorturl.at/2breu

Very good https://shorturl.at/2breu

Awesome https://shorturl.at/2breu

Very good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Awesome https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://lc.cx/xjXBQT

Good https://t.ly/tndaA

Very good https://t.ly/tndaA

http://terios2.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4779

http://terios2.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4786

Awesome https://urlr.me/zH3wE5

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

https://vitz.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5029

https://myteana.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6840

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Awesome https://is.gd/N1ikS2

Very good https://is.gd/N1ikS2

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5309

http://passo.su/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4271

https://honda-fit.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=7126

http://terios2.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4647

https://mazda-demio.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6359

https://honda-fit.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=7056

https://hrv-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6937

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5454

http://toyota-porte.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=3355

http://toyota-porte.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=3372

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5467

Даня Милохин & Николай Басков – Дико тусим скачать песню бесплатно в mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/XbLuF

Anivar – Падает Звезда скачать mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/7ONEA

Денис Майданов – Пролетая над нами скачать бесплатно mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/PoFcz

Nataliya – Бармен, Налей (Ben Bright Remix) скачать песню в mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/UNSUE

Подиум – Танцуй, пока молодая скачать песню на телефон и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/3r6UD

Натали – Новогодние игрушки скачать и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/x60Qi

MC Zali & Julia Lois – Сеньорита скачать песню бесплатно в mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/J7UxY

Awesome https://shorturl.fm/5JO3e

Cool partnership https://shorturl.fm/a0B2m

Very good partnership https://shorturl.fm/68Y8V

Cool partnership https://shorturl.fm/XIZGD

https://telegra.ph/Istoriya-formata-MP3–revolyuciya-v-mire-cifrovoj-muzyki-03-13

http://passo.su/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4256

https://vitz.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5071

https://mazda-demio.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6358

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5278

https://honda-fit.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=7147

https://shorturl.fm/A5ni8

https://vitz.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5098

https://shorturl.fm/a0B2m

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5355

https://shorturl.fm/bODKa

https://shorturl.fm/9fnIC

https://shorturl.fm/YvSxU

https://shorturl.fm/bODKa

https://shorturl.fm/a0B2m

https://shorturl.fm/YvSxU

https://shorturl.fm/oYjg5

https://shorturl.fm/6539m

https://shorturl.fm/A5ni8

https://shorturl.fm/a0B2m

https://shorturl.fm/9fnIC

https://shorturl.fm/a0B2m

MORGENSHTERN – Новый Мерин скачать песню на телефон и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/Fqwdb

Sevenrose – Верила скачать песню и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/dYMGS

Мари Краймбрери – Не Буди Меня скачать песню в mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/XfcC9

Lx24 – Шаг Вперёд Два Назад скачать mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/oxY04

Romanova – Караван (ZIIV Remix) скачать mp3 и слушать онлайн бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/fOByR

Dim – Верь Мне скачать песню и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/NFHix

Таисия Повалий – Родина скачать песню и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/IasUx

Антон Балков – Помадой скачать песню и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/mxaTf

ANSE – Лунатики скачать и слушать песню бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/UdYdk

https://shorturl.fm/oYjg5

https://shorturl.fm/oYjg5

https://shorturl.fm/FIJkD

https://shorturl.fm/9fnIC

https://shorturl.fm/5JO3e

https://shorturl.fm/FIJkD

https://shorturl.fm/j3kEj

https://shorturl.fm/LdPUr

Дмитрий Маликов – Ты одна, ты такая скачать mp3 и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/aDGqZ

Денис RiDer – Двигаться (Nejtrino & Baur Remix) скачать песню бесплатно в mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/1y1QJ

Рада Рай Feat. Алексей Петрухин – Рвутся Cтруны скачать песню и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/O0eCn

Элени – Мирабо скачать бесплатно и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/19yFr

Таисия Повалий – Я знаю, что ты знашь скачать песню на телефон и слушать бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/mYdV7

Эдуард Иконников – Ты Забегай Ко Мне скачать бесплатно mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/yD0EY

Тамара Кутидзе – Зимняя Ягода скачать и слушать песню бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/sD2UO

Воскресенский – Пацанов Губит Любовь скачать mp3 и слушать онлайн бесплатно https://shorturl.fm/P0qrE

В. Маркин – Колокола скачать mp3 и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/rDDy5

Mseven – Холодное Сердце скачать и слушать онлайн https://shorturl.fm/VZuqS

https://shorturl.fm/TDuGJ

https://shorturl.fm/Xect5

https://shorturl.fm/I3T8M

https://shorturl.fm/IPXDm

https://shorturl.fm/DA3HU

https://shorturl.fm/JtG9d

https://shorturl.fm/MVjF1

https://shorturl.fm/JtG9d

https://shorturl.fm/0oNbA

https://shorturl.fm/fSv4z

https://honda-fit.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=7050

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5395

https://honda-fit.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=7326

https://mazda-demio.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=6514

http://passo.su/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4262

http://wish-club.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=5233

http://terios2.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4704

http://terios2.ru/forums/index.php?autocom=gallery&req=si&img=4732

NEEL – Намекаю скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/3282-neel-namekaju.html

Bukatara – Невеста скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/3157-bukatara-nevesta.html

Qiiza – Танцевать в Темноте скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/3284-qiiza-tancevat-v-temnote.html

MATANYA – Пой скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/3012-matanya-poj.html

Reya – Всё Ещё Мне Больно скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/2928-reya-vse-esche-mne-bolno.html

DAASHA – Спать С Тобой скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/2925-daasha-spat-s-toboj.html

ASAFY – Останови скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/2773-asafy-ostanovi.html

Потап и Настя – Голуби скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/2576-potap-i-nastja-golubi.html

OWEEK, Ханза – Вечеринка скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/2565-oweek-hanza-vecherinka.html

Daboguvushi Feat. & Lil Miroir & Mark Wazze – Не Исчезай скачать песню и слушать онлайн

https://allmp3.pro/3150-daboguvushi-feat-lil-miroir-mark-wazze-ne-ischezaj.html